Overview

Two dams were constructed on the Elwha river in the early 1900's, blocking salmon from coming up the river to spawn and creating two reservoirs behind the dams. They originally powered part of Port Angeles, but eventually only powered a small paper and pulp mill. The dams were opposed by many groups, but supported by others. Through open-mindedness, all parties involved with the dams were able to come to a compromise in taking down both dams and restoring the Elwha River's original path, consequently allowing salmon to return upstream to spawning ground.

The Elwha River has a long history, and much of it was made possible by the leaders who used their voices for change. Below is an exploration of the Elwha River's history with a focus on leadership.

The Elwha River has a long history, and much of it was made possible by the leaders who used their voices for change. Below is an exploration of the Elwha River's history with a focus on leadership.

Before the Dams

1885- The Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe signs the Treaty of Point No Point, ceding ownership of the land surrounding the Elwha river to the US Government. In their treaty, the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe gains certain fishing rights.

1885- The Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe signs the Treaty of Point No Point, ceding ownership of the land surrounding the Elwha river to the US Government. In their treaty, the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe gains certain fishing rights.

Age of the Dams

September 1910- Thomas Aldwell begins construction on the Elwha Dam. He sees an issue in the lack of power in Port Angeles, and takes initiative to fix this problem. He starts work on a dam that will provide clean, hydroelectric power to the city. However, the dam is built without fish passage, which violates state law.

September 1911- As soon as one year after construction on the dam began, salmon disappear entirely from the river above the Elwha Dam.

1914- Generation begins at the Elwha Dam. Aldwell faced many trials to get the dam up and running. He had to overcome a dam blowout and flood. Also, the dam did not include a fish passage, which was required by state law. He instead put in a fish hatchery. Aldwell showed persistence in trying to solve a problem for his city.

1922- The fish hatchery built to compensate for lack of a fish passage proves to be continually unsuccessful and is shut down.

1924- Congress declares Native Americans to be United States citizens. The Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe gains rights, which allows them to be even more vocal against the dams.

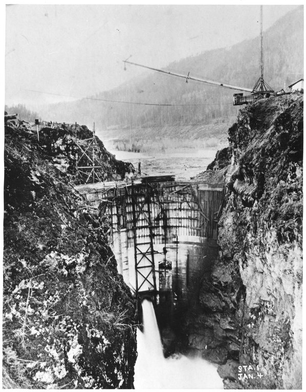

May 1927- Glines Canyon Dam is finished and begins generation after just one year of construction.

September 1910- Thomas Aldwell begins construction on the Elwha Dam. He sees an issue in the lack of power in Port Angeles, and takes initiative to fix this problem. He starts work on a dam that will provide clean, hydroelectric power to the city. However, the dam is built without fish passage, which violates state law.

September 1911- As soon as one year after construction on the dam began, salmon disappear entirely from the river above the Elwha Dam.

1914- Generation begins at the Elwha Dam. Aldwell faced many trials to get the dam up and running. He had to overcome a dam blowout and flood. Also, the dam did not include a fish passage, which was required by state law. He instead put in a fish hatchery. Aldwell showed persistence in trying to solve a problem for his city.

1922- The fish hatchery built to compensate for lack of a fish passage proves to be continually unsuccessful and is shut down.

1924- Congress declares Native Americans to be United States citizens. The Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe gains rights, which allows them to be even more vocal against the dams.

May 1927- Glines Canyon Dam is finished and begins generation after just one year of construction.

Age of Voices

1938- Congress establishes Olympic National Park, including Glines Canyon Dam within its limits.

1968- Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe's reservation is established. Before this time, the tribal members were displaced by Port Angeles settlers. Although the federal government purchased land for the tribe in 1935, it was not put into reservation status until now.

1986- Klallam Tribe and environmental groups petition for dam removal. Many groups intervene in the re-licensing process and petition for removal of both dams. These groups include the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe, Seattle Audubon Society, Friends of the Earth, Sierra Club and Olympic Park Associates. They show leadership in speaking out to protect what is important to them- their homes and environments.

1989- Klallam Tribe obtains grant to begin studies for dam removal. Their findings will allow them to support their petitions for dam removal.

1990- Federal government begins to study dam removal.

October 1992- President George H.W. Bush signs the Elwha River Ecosystem and Fisheries Restoration Act. He, along with Congress, show leadership in allowing the Department of Interior to purchase both dams and take charge of restoring the river and salmon habitat.

1993- The Department of Interior completes a study determining that both dams must be removed in order to restore the fish habitat.

1994- Opposition to planned dam removal grows. Rescue Elwha Area Lakes (REAL) raise questions about the effects of the dam removal. Their worries include flooding, recreation, and habitat destruction of the trumpeter swan. REAL is trying to preserve the current environment and protect the lacustrine (lake) wildlife, whereas the anti-dams groups want to return the environment to its original state and expand habitat for riparian (river) wildlife. Both groups are trying to do what they think is best for the Elwha Valley.

1938- Congress establishes Olympic National Park, including Glines Canyon Dam within its limits.

1968- Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe's reservation is established. Before this time, the tribal members were displaced by Port Angeles settlers. Although the federal government purchased land for the tribe in 1935, it was not put into reservation status until now.

1986- Klallam Tribe and environmental groups petition for dam removal. Many groups intervene in the re-licensing process and petition for removal of both dams. These groups include the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe, Seattle Audubon Society, Friends of the Earth, Sierra Club and Olympic Park Associates. They show leadership in speaking out to protect what is important to them- their homes and environments.

1989- Klallam Tribe obtains grant to begin studies for dam removal. Their findings will allow them to support their petitions for dam removal.

1990- Federal government begins to study dam removal.

October 1992- President George H.W. Bush signs the Elwha River Ecosystem and Fisheries Restoration Act. He, along with Congress, show leadership in allowing the Department of Interior to purchase both dams and take charge of restoring the river and salmon habitat.

1993- The Department of Interior completes a study determining that both dams must be removed in order to restore the fish habitat.

1994- Opposition to planned dam removal grows. Rescue Elwha Area Lakes (REAL) raise questions about the effects of the dam removal. Their worries include flooding, recreation, and habitat destruction of the trumpeter swan. REAL is trying to preserve the current environment and protect the lacustrine (lake) wildlife, whereas the anti-dams groups want to return the environment to its original state and expand habitat for riparian (river) wildlife. Both groups are trying to do what they think is best for the Elwha Valley.

Age of Restoration

2000- The U.S. Department of Interior purchases both dams for $29.5 million.

2004- Elwha Restoration Project is allowed to go forward. Together, the City of Port Angeles, the National Park Service and the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe create a contract that all parties agree to. This contract authorizes the $182 million Elwha Restoration Project to go forward. All parties were open-minded about this issue and were flexible in coming to a consensus.

June 2011- Generation stops at both dams.

September 2011- Dam removal begins.

August 2014- Dam removal is completed.

2000- The U.S. Department of Interior purchases both dams for $29.5 million.

2004- Elwha Restoration Project is allowed to go forward. Together, the City of Port Angeles, the National Park Service and the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe create a contract that all parties agree to. This contract authorizes the $182 million Elwha Restoration Project to go forward. All parties were open-minded about this issue and were flexible in coming to a consensus.

June 2011- Generation stops at both dams.

September 2011- Dam removal begins.

August 2014- Dam removal is completed.

Today

Both dams have come down and Lake Aldwell and Lake Mills resevoirs have been drained. A new hatchery has been built to supplement the salmon population. Fortunately, salmon have begun to return up the Elwha and vegetation has begun to grow. There are still problems to be solved and questions to be answered, but the Elwha is certainly off to a good start on the road to recovery.

For more information on the Elwha's current state, visit the National Parks Services' website or the Klallam Tribe's website

For an interactive timeline of the Elwha River's story, check out the Seattle Times' Elwha Report

Both dams have come down and Lake Aldwell and Lake Mills resevoirs have been drained. A new hatchery has been built to supplement the salmon population. Fortunately, salmon have begun to return up the Elwha and vegetation has begun to grow. There are still problems to be solved and questions to be answered, but the Elwha is certainly off to a good start on the road to recovery.

For more information on the Elwha's current state, visit the National Parks Services' website or the Klallam Tribe's website

For an interactive timeline of the Elwha River's story, check out the Seattle Times' Elwha Report

Credits

Image Credits

(in order of appearance)

Asahel Curtis, courtesy of Washington State Historical Society

Nippon Paper Group

National Parks Services

Lower Klallam Tribal Library

Resources

Seattle Times

Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe

Image Credits

(in order of appearance)

Asahel Curtis, courtesy of Washington State Historical Society

Nippon Paper Group

National Parks Services

Lower Klallam Tribal Library

Resources

Seattle Times

Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe